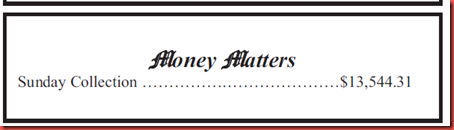

No numbers report for Decemeber 27, 2015

Francis X. Clooney, SJ | Dec 18 2015 - 10:41am | 9 comments

I appreciate the considerable interest among readers of these posts, many by personal email, and some posted at the America site. Excepting a few commenters who appear too eager to draw conclusions—about Islam, about me—I appreciate the posts, including those who want to read the Quran differently, with differing views on mercy or violence in the Quran. (I am also grateful to the reader who pointed out that the volume does contain an essay toward an Islamic theology of religions, Joseph Lumbard’s “The Quranic View of Sacred History and Other Religions,” a beautiful essay worthy of close reading.)

As I have said each time, my point is not that we agree, but that we who are not Muslim educate ourselves on these matters, resist caricatures of Muslims and be open, ideally, also entering into conversation with Muslim neighbors likewise open to studying the Bible. While such a community of readers will not push aside headlines dominated by the Trumps and the ISIS supporters of this world, we will in the long run make the greater difference.

Given that we are deep into Advent, I thought it fitting now to explore The Study Quran on the theme of Mary, Mother of Jesus. The ample index tells us that there are more than 50 references to Jesus in the Quran, and more than 15 to Mary. They are mentioned in the editors’ commentary many more times, as the index shows us. The editors point out that Mary is the only woman named in the Quran; while most such named figures are prophets, there is debate about Mary’s status, some listing her among the prophets, others preferring to say that she is “an exceptionally pious woman with the highest spiritual rank among women” (763).

They add that in a hadith (traditional saying), “the Prophet names Mary as one of the four spiritually perfected women of the world,” (763) who will “lead the soul of blessed women to Paradise” (143). In Sura 66 (Forbiddance), Mary is evoked again respectfully, “the daughter of Imran, who preserved her chastity. Then We breathed therein Our Spirit, and she confirmed the Words of her Lord and His Books; and she was among the devoutly obedient” (66:12). One commentator, Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, takes this to mean that Mary “believed in all previous revelations.”

I need not deny that other passages diverge further from Christian faith, yet without disrespect for Mary and Jesus. In Sura 5 (The Table Spread), for example, we read, “The Messiah, son of Mary, was naught but a messenger—messengers have passed away before him. And his mother was truthful. Both of them ate food. Behold how We make the signs clear unto [the People of the Book]; yet behold how [those signs] are perverted.” The commentary notes that the Prophet Mohammed is described in the same way in Sura 3:144: “Mohammed is naught but a messenger; messengers have passed before him.”

The commentary adds, “The assertion in this verse that both Mary and Jesus ate food is meant to affirm their full humanity and refute those who see them as divine. Of course, Christian theology also sees Christ as ‘fully human’ and ‘fully divine,’ and the Quranic view of Jesus as fully human is consistent with certain verses of the New Testament, such as Luke 18:19 and Philippians 2:6-8, which stress Jesus’ humanity in relation to God.” That Mary was “truthful” places her in the company of the prophets; she is the one who testifies to “the truth of Jesus’ prophethood and message.”

In Sura 3 (The House of Imran), Mary is introduced as the daughter of Imran and his wife, who prays, “I have named her Mary, and I seek refuge for her in Thee, and for her progeny, from Satan the outcast.” (3:36) Mary is then placed by the Lord under the care of Zachariah, father of John. This version of the Annunciation follows:

The commentary reports how this Sura, on Mary and Jesus and other prophets, once helped save the lives of Muslim refugees under the protection of the Christian Negus (king) of Abyssinia. A Makkan delegation had come and demanded that the refugees be turned over for execution. The Negus asks that first a Sura of the Quran be recited. When part of this Sura is recited, “the Negus and the religious leaders of his court began to weep profusely and refused to hand over the Muslims, indicating that the religious teachings of the Quran were deeply related to those of the Christian faith.” Is it not so very right, that Scripture might inspire those in power to protect rather than abandon those in dire need, even if they are of another faith?

The commentary also points out the stylistic unity and harmony of this Sura; it is one that you may wish to listen to, if you have never heard Quranic recitation. I found this recitation pleasing to the ear, though I do not know Arabic. Or you may wish to go more slowly with a version that includes a translation.

That I highlight in this way some of the passages dealing with Mary in the Quran is by no means a novel idea. Readers interested in more on Mary, Jesus and other biblical figures in the Quran, can turn to John Kaltner’s Ishmael Instructs Isaac: An Introduction to the Qur’an for Bible Readers (1999). That Mary can even today be a powerful protector and nurturer of Muslim and Christian unity was well expressed in 1996 by Cardinal William Keeler. Similarly, in 2014 Fr. Miguel Angel Ayuso, secretary of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, highlighted the great importance of Mary in Muslim-Christian dialogue.

Can we not imagine that in this Jubilee Year of Mercy, Mary will help refugees across closed borders, and open the hearts of gatekeepers who would close the door on people who live by the holy Quran? As Pope Francis wrote when he declared the jubilee year of Mercy,